Liveability and Urban Renewal 3.0

14 10 2020Updated in English on 3-2-2021, original version in Dutch below

When French officials were shown around Kanaleneiland in Utrecht as part of an exchange programme on troubled neighbourhoods, they were flabbergasted. Lots of green space, plenty of amenities and beautiful real estate. Perhaps the crime rate was relatively high, but this was nothing like the banlieues around Paris the French officials had in mind. It remains however essential to commemorate that this is neither a given nor a coincidence, but a direct consequence of the rich history of Dutch urban renewal. We believe it is time to continue this path, but to do it even better this time around.

During the 1970s, the Netherlands saw its first wave of urban renewal. Combating urban deprivation and physical impoverishment was part and parcel of this initiative. A country-wide renovation wave (avant-la-lettre) helped to tackle this problem. In the decades that followed, policymakers broadened their horizons and used new urban renewal efforts to reduce social problems in deprived neighbourhoods to its city’s average (Urban Renewal 2.0). Now that the concentration of these problems is increasing again in some neighbourhoods, experts are arguing Urban Renewal 3.0: an integrated approach that also pays attention to the specific role a neighbourhood plays in its city.

Bottom-up method

As Springco’s company philosophy prescribes, we start looking for a way to shape this third wave of urban renewal from the bottom up. First, it is necessary to monitor lots of data about a neighbourhood’s performance. This goes from education scores (CITO, equivalent to A-levels) to the relative number of companies that are launched. The local context then determines the nature of the social problems, and eventually a customised solution. While an enhancement of the labour market participation of school-leavers is most urgent in neighbourhood A, it could well be that reducing the crime rate would have a far bigger impact in neighbourhood B.

We therefore search for look-a-likes of 300 neighbourhoods that are at risk of deprivation. These look-a-likes would have a similar physical structure, but a much better performance across most of the social indicators. Considering Tobler’s first law of geography – “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” – we allocate weight to the location of the look-a-likes: in order to comply with our demands, they could not be too far away. Besides that, the algorithm is given complete freedom. Ultimately, the key question is: Why are these neighbourhoods performing better, while they look the same?

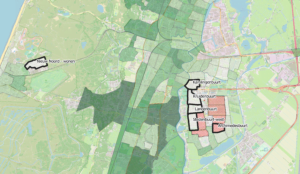

Archimedesbuurt and its five ‘look-a-likes

Context-specific policies

In the fictional case of the Archimedesbuurt in Haarlem, we find five look-a-like neighbourhoods, as shown on the map above. Further analysis shows that the largest gap between the Archimedesbuurt and its look-a-likes is in the field of social participation and debt counselling. At the same time, the Archimedesbuurt is already performing well in the areas of housing, economy and education. Based on this information, context-specific urban renewal can be carried out with measures that match the local needs. We are working with our partner Rebel to develop a social cost-benefit analysis for these measures.

Where Urban Renewal 2.0 was based on a city average when developing policy, we can now deliver a more customized solution in Urban Renewal 3.0. Springco and Rebel believe in data-driven and bottom-up policymaking, in which the context of each place and each individual is valued.

Stadsvernieuwing 3.0

(zoals gepubliceerd op 14 oktober, 2020)

Toen Franse ambtenaren als onderdeel van een uitwisselingsprogramma over probleemwijken ons Kanaleneiland bezochten, keken ze vertwijfeld om zich heen. Veel groen, een rustige buurt en mooi vastgoed. Ja, ook in Nederland hebben we wijken met problemen. Maar we hebben geen banlieues. Dat we geen banlieues hebben is geen toeval, maar een rechtsreeks gevolg van Neerlands rijke geschiedenis van stedelijke vernieuwing.

Tijdens de jaren ’70 stond hierbij de bestrijding van fysieke verpaupering centraal (Stadsvernieuwing 1.0) en in de decennia daarna was beleid erop gericht ook sociale problematiek tot het stedelijk gemiddelde terug te dringen (Stadsvernieuwing 2.0). Nu de concentratie van problemen achter de voordeur in sommige buurten weer toeeneemt pleit het Forum voor Stedelijke Vernieuwing voor een volgende slag met Stadsvernieuwing 3.0: een integrale aanpak waarin ook aandacht is voor de functie die een wijk heeft in de stad.

Bottom-up stadsvernieuwing

Zoals onze bedrijfsfilosofie voorschrijft zijn wij op zoek gegaan naar een manier om deze Stadsvernieuwing 3.0 van onderaf vorm te geven. Dit betekent dat eerst in beeld moet worden gebracht wat per wijk de opgave is, want de lokale context is bepalend voor de aard van multiproblematiek. Waar de ene wijk behoefte heeft aan betere onderwijsprestaties en hogere arbeidsparticipatie van schoolverlaters kan vermindering van criminaliteit juist van grote invloed zijn in een andere wijk.

Voor 300 kwetsbare stadsbuurten zijn we op zoek gegaan naar look-a-likes. Wijken met een vergelijkbare fysieke opbouw, maar veel betere maatschappelijke prestaties. Omwille van Toblers eerste wet van de geografie – “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” – hebben we de computer meegegeven rekening te houden met de locatie van de look-a-likes. Die moeten enigszins in de buurt zijn. Maar verder kreeg het algoritme alle vrijheid. Uiteindelijk was de hamvraag natuurlijk: Waarom presteren deze wijken nou beter, terwijl ze er hetzelfde uitzien?

Locatiegerichte maatregelen

Voor de Archimedesbuurt in Haarlem werden vijf vergelijkingsbuurten binnen de corop-regio gevonden, zoals weergegeven op de bovenstaande kaart. Nadere analyse leert dat het grootste gat met die buurten ligt op het gebied van sociale participatie en schuldhulpverlening, terwijl de Archimedesbuurt het op de gebieden wonen, economie en onderwijs gewoon goed doet. Op basis van die informatie kan context-specifiek worden gestuurd met maatregelen die aansluiten bij de lokale behoefte. Momenteel zijn we met onze partner Rebel bezig met een maatschappelijke kosten-baten analyse voor deze maatregelen.

Waar Stadsvernieuwing 2.0 bij het opwaarderen van een wijk nog uitging van stedelijke gemiddeldes, kunnen we dankzij moderne technologische ontwikkeling bij Stadsvernieuwing 3.0 veel meer maatwerk leveren. Springco gelooft in bottom-up beleid maken, waarin de uniciteit van elke plek en ieder individu op waarde wordt geschat.